I spent the morning at the movie theatre watching the Live at the Met production of Alvin Berg’s opera Lulu staged by William Kentridge (thanks Gillian and Arta for coming with me!) Here is the trailer. It was four hours of what felt like an atonal musical assault.

Maybe that seems a bit unfair. It was amazing. I loved it. But I also left it feeling wrung out. It left me thinking about the narrative story, the visual field and the musical soundscapes. There was much there that was unexpected. In the face of everything unexpected, I felt very much grounded in the experience of the story.

- Louise Brooks as Lulu in Pandora's Box

For maybe ten years, I taught a Law and Film Course using Pabst’s 1928 silent film classic, Pandora’s Box, which is also the story of Lulu. The arc of the story in both the opera and the film is similar. Lulu, a femme fatale, is taken in by (and 'takes in') man after man. Always, Death follows in her wake. In the end, Jack the Ripper has to be brought into finally quell the threat that she poses to men and women in the world around her. As Orit Kamir points out in her excellent analysis of the film (in her book, Framed: Woman in Law and Film), it is as if one serial killer has to be brought in to finish off another.

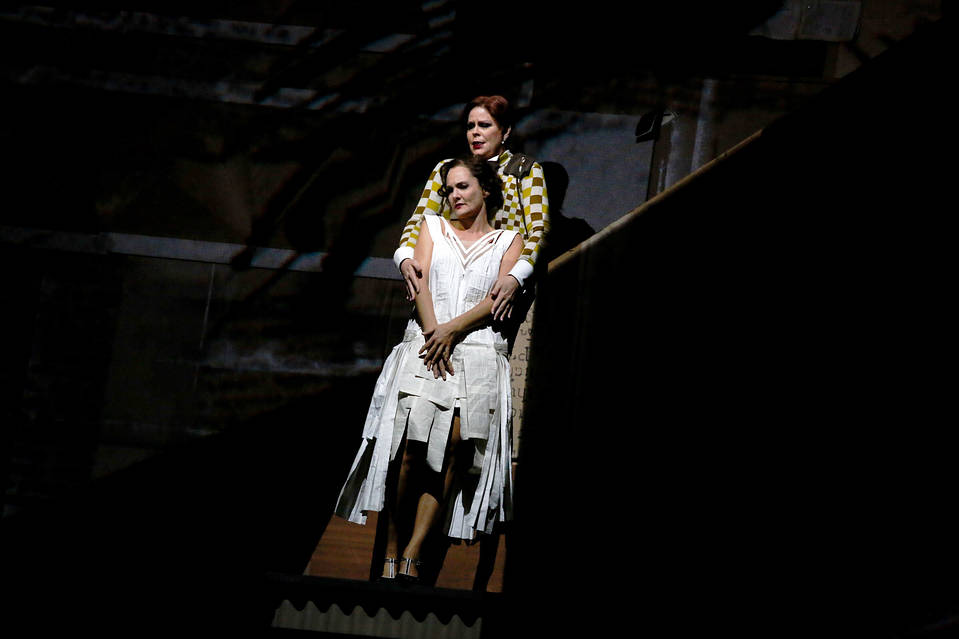

- Lulu dancing with the Countess Geschwitz

Having seen the movie so many times, I was prepared for the narrative which situates woman as Pandora, as responsible for the introduction of desire, disease and death all around her. No surprise. Fabulous story for feminist analysis. But today was my first experience with Berg's adaptation of the story.

Of course, musically, it is a complicated piece of work. Not much in the way of easy melodies, or catchy tunes to carry you through. But it was not just the difficulty of the music. There was also so much that was unexpected in the production. The visual field was staggering. The back stage was used cinematically with layers of film, newspaper texts and images whipped on and off throughout the piece. Opera these days is always subtitled, so I am accustomed to reading the libretto text, so it was not really a big deal that the opera is in German. But I did feel conscious of how rapid my eye movements were because of how lush the background scene was, how rapidly the images moved and how it drew my eyes away from the narrative text up to the visual field. It was a visual field that completely matched German expressionist painting style of the ‘30’s. But it was cinematic, and always in motion. And as my eyes were continually being pulled across the stage, i could feel a matching rise in discomfort in my body. I suppose in some ways that is what I mean when saying it was an assault both of sound and of image.

The opera is astonishingly visceral. It does operate in multiple registers. In addition to the musical language, and the visual field of cinematic expressionist art, there are two characters who are silently on stage throughout.

- Joanna Dudley, holding a position in Lulu

So, for example, when Lulu is seducing the artist behind a screen, Joanna Dudley's character is out front, sliding her stocking up and down, spreading her legs open and closed, and weaving her body in ways that suggest a dance of sexual seduction, a dance that carries the feeling of 1930’s German expressionism. There is a certain angularity and almost a violence of line in her body and movements. Throughout the opera the movements of the dancer, of this 'interior Lulu', are marked by this sense of hold, legs askew in certain positions and very uncomfortable positions held with a sense of agony or tension, that as a viewer I kept noticing I was feeling in my own body, the discomfort of the hold. This resonates with Kendrick's decision to show Lulu throughout the opera with a piece of paper covering her heart with an ink line drawing of a breast - but which is its stylization, also appears as an inverted fermata, the musical indicator “to hold.” Again, the feeling of the silence was almost physically violent at times. It was almost like an interior psychological space, exhausting watching the bodies contort and be held in stillness. It is like a third language being played out on the stage.

I was particularly struck by one difference between the film and the opera. In the cinematic version, the Countess Geschwitz sacrifices herself for Lulu in order to enable her to escape to London. In the operatic version, the Countess Geschwitz stays close to Lulu to the end. The Countess, like many of the men who swirl around Lulu, is also desperately in love, a love that Lulu never requites.

- Geschwitzt pledging to save Lulu

Near the end, as Lulu takes another customer to her bed, a customer whom we as the audience suspect to be Jack the Ripper, Geschwitz remains on stage, singing. Having considered throwing herself into the river or hanging herself, she determines to go on, to leave her broken heart behind, to return to Germany, to enrol herself in the university, to study law (you heard that right...Law!?) and take up the fight for women’s rights.

After Geschwitz has articulated this decision, we hear Lulu scream, and see the backdrop screen is covered by splatters of India ink, like blood. The murderer comes out from behind the screen and then also kills stabs Geschwitz in the belly, expressing himself to be a lucky man to have had such a chance (two victims, not just one). Even more than with Pabst's film, Berg's opera captured such a field of woman-hating. Leaving the theatre, feeling the exhaustion of the musical and visual assault, I found myself thinking about the profound woman hating that structures both the opera and the film. Of course, many of the men around Lulu also die, but there was something quite powerful about the final scene involving this double killing of the embodied sexuality of a woman and the embrained core as well through Geshwitz: the act a denial of the productive agency of either a woman’s body or mind.

Of course, a person can read a film or an opera against the grain. I think it is certainly possible to read this film with great affection for Lulu and indeed to see her as a powerful character asserting her own will and her own morality, against the pattern of constraints and limits on her. She gives freely, both her sexuality and her money, but reserves the right to make her own choices about when she will or will not give those gifts. The background screen both captures something of the cruelty in the text, the cruelty of inter-war Germany, maybe even inter-war Europe to be precise, and the cruelty of the world of erasure in which Lulu lives. She is constantly misnamed by those around her: Mignon or Eve. And the text makes visible the ways in which she is a shifting object constructed by the desire of all of those who circle around her. You don’t have to go too far into psychoanalytic theory to find these themes. But the backdrop does make visible the ways she is a projection of those around her and made to pay for the gap felt by those who seek her to grasp something in her that they themselves had tried to place there. The opera foregrounds commodification, set in the period of the economic crash which mirrors nicely the fact of value itself being a projection, rather than a tangible thing. Very much like Lulu is read by those around her.

The music student in me sees that the opera was lush, beautiful and there is every reason to see it. Marlis Peterson, like Louise Brooks in the cinematic version, completely occupies the role. At the same time, the significant woman-hatingness of the piece left me reflecting on strategies that different people use in the face of cultural narratives that carry such deep distain for and fear of women. What would it mean to just turn away from these stories? I am not sure there would be any opera left to see if a person took that approach seriously. Maybe the best one can do is read the story in a way which makes visible the ways that these narratives, while projections, are none the less projections with tangible consequences.

No comments:

Post a Comment

If you are using a Mac, you cannot comment using Safari. Google Chrome, Explorer or Foxfire seem to work.